Toby Hambly

Shutterstock: By Firat Cetin

This May marks 30 years since a particularly damaging piece of legislation was passed. Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 reads as follows – ‘A local authority shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality’ or ‘promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.’

Repealed in Scotland in 2000 and three years later in England and Wales, the law would never be used in a court. Despite applying specifically to local authorities and not schools per se, the effects of the law would be most acutely felt by teachers and pupils. To provide me with some context I spoke with Dr James Methven, currently the head of English at Uppingham School. What became immediately apparent to me was how virulently homophobia had inhabited all levels of British public life. I, and maybe others of my generation, have a tendency to be naïve about how recently discrimination was manifested not just in society but in law. We congratulate ourselves on milestones without seeing the proper context. We are taught that women got the vote in 1918 and we celebrate the centenary – not burdening ourselves with the fact that suffrage was extended only to women over 30 who held £5 of property. Symbolic victories are important but they shouldn’t obscure the wider struggles that persist.

The spectre of the HIV/AIDS epidemic contributed to the vitriol and stigma faced predominantly by homosexual and bisexual men. It bolstered various sections of society in their convictions about sexuality and provided an easy pointscoring opportunity for anti-gay politicians. History shows that homophobia and other discriminatory ideas grow markedly in uncertain times. In this vein, the Tory party consciously latched onto the climate of 1980s Britain. In her speech to the party conference in Blackpool on 9 October 1987 Margaret Thatcher said, “Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay,” before concluding to rapturous applause, “all those children are being cheated of a sound start in life.” Dr Methven recalled a similar example, telling me “There was a senior policeman, James Anderton, who in December 1986 commented that drug addicts, prostitutes and homosexuals who have HIV/AIDS were ‘swirling in a human cesspit of their own making’.” James Anderton was chief constable of Greater Manchester police until 1991 and was knighted in the previous year. Documents released in 2012 showed that the controversial policeman was protected from public inquiry by the deliberate and concerted efforts of Margaret Thatcher herself.

The spectre of the HIV/AIDS epidemic contributed to the vitriol and stigma faced predominantly by homosexual and bisexual men. It bolstered various sections of society in their convictions about sexuality and provided an easy pointscoring opportunity for anti-gay politicians. History shows that homophobia and other discriminatory ideas grow markedly in uncertain times. In this vein, the Tory party consciously latched onto the climate of 1980s Britain. In her speech to the party conference in Blackpool on 9 October 1987 Margaret Thatcher said, “Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay,” before concluding to rapturous applause, “all those children are being cheated of a sound start in life.” Dr Methven recalled a similar example, telling me “There was a senior policeman, James Anderton, who in December 1986 commented that drug addicts, prostitutes and homosexuals who have HIV/AIDS were ‘swirling in a human cesspit of their own making’.” James Anderton was chief constable of Greater Manchester police until 1991 and was knighted in the previous year. Documents released in 2012 showed that the controversial policeman was protected from public inquiry by the deliberate and concerted efforts of Margaret Thatcher herself.

Section 28 is a stitch somewhere towards the end of the long tapestry of our social and political attitudes towards sexual otherness. With the age of consent set at 21, homosexual sex was partially decriminalised in 1967 – about 15 years after the enigma code-breaker Alan Turing was convicted of gross indecency and chemically castrated. Certainly a milestone, however homosexual sex was legal only under the specific exemption that ‘a homosexual act in private shall not be an offence provided that the parties consent thereto and have attained the age of twenty-one years’. All other ways in which the law could be brought to bear on homosexuality remained.

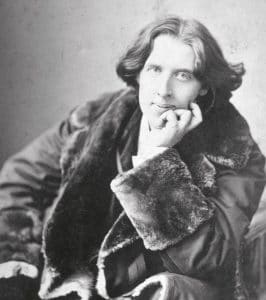

The age of consent was lowered to 18 under John Major’s government in 1994 before achieving parity with heterosexual sex in 2000, 100 years to the day after the death of Oscar Wilde. On this Dr Methven told me, “The Sun in 2000 declared the equalisation of sexual choice as a ‘pervert’s charter’ in the same way that originally when homosexuality was outlawed in 1885 it was described as a ‘blackmailer’s charter’.” It is not known whether or not The Sun was aware of this in its choice of words, nor is it clear in my mind as to which scenario would have been better.

The legal ramifications of Section 28 have been non-existent because there has not been a single prosecution under its auspices. The real insidiousness resulted from its ambiguity. Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin was an innocuous children’s book published in 1983 about a girl, Jenny, who lived with her father and his gay lover. This book became the bête noire of backbench Conservative MPs who argued that left-wing councils were attempting to disseminate gay propaganda. This focus on schools, despite the Department of Education’s consistent position that Section 28 did not affect schools at all, was what led to anxiety and self-censorship amongst teachers.

Dr Methven told me of one such situation early in his career: “I remember quite specifically we had a visiting speaker come one day to talk about poetry and there was some concern from other staff who were at the forum that he was talking openly about the prospect of bisexuality in an Elizabethan sonnet … I was de facto hosting and I just signalled that it was OK and told him to carry on. It hadn’t occurred to me that we were doing anything illegal by openly discussing the possibility that one could read this in a queer way.” I asked him if there was some cognitive dissonance required to continue teaching in the best interests of the students whilst being impeded in this fashion. “Yes I think there is,” he began, “I’m busy teaching literature and if it contains material which needs to be fully explicated and you’re told you may not then obviously you’re stuck. You have to think in an ageappropriate fashion – you wouldn’t over-expand upon or over-explain sexual material to a younger age group anyway. But by the time you’re studying texts at sixth form level you’d hope that people are mature enough to cope.”

Because the law was never used in a prosecution, the words ‘promote’, ‘acceptability’ or ‘pretended family relationship’ were never given proper definition. Even without legal clarification these terms illustrate a creeping semantic underhandedness. That homosexuality is a doctri ne or lifestyle choice is a notion at the core of the misunderstanding of sexuality and illuminates the pernicious alleged association between homosexuality and paedophilia. Throughout modern history this supposed link has been used to convict and imprison homosexuals and crush the potential of groups concerned with supporting young people struggling with their sexuality.

ne or lifestyle choice is a notion at the core of the misunderstanding of sexuality and illuminates the pernicious alleged association between homosexuality and paedophilia. Throughout modern history this supposed link has been used to convict and imprison homosexuals and crush the potential of groups concerned with supporting young people struggling with their sexuality.

My politics teacher at school once told me that in a liberal democracy, one’s right to punch another in the face ends where the nose begins. The law exists to remedy identifiable harm. This isn’t a bad summation of the general British sense of privacy but one that Section 28 clearly flouts. If not a single prosecution was brought under Section 28 of the Local Government Act, then we can reasonably conclude that there was no specific harm. Furthermore, if after its repeal there was not a sudden influx of salacious material or spike in ritual grooming, then we can assume that there was never a need for this law in the first place. It existed to further the political and social aims of one group against the sanctity and future of another more marginalised one.

The supposed harm in this case – that children were being wrongly taught that homosexuality was normal – was deliberately conflated with the language of identity politics causing the issue to be obfuscated under a blanket of mutual recrimination. The primary objective of this political tactic is to recast the subject and link it to much more nebulous concepts like the family, morality or religion. The same tactic was used against the suffragettes, claiming that women voting would tear at the fabric of society and dissolve the family unit. The fight over Section 28 followed this choreography, metastasising to a broader culture war between generally ‘progressive’ and ‘traditional’ camps.

If you were to print the 1988 Local Government Act you would have 54 pages of solid text, of which half of one page would be taken up by Section 28 – less than 1%. Yet its legacy has undoubtedly affected the lives of thousands upon thousands of people. From teachers like Dr Methven just trying to get on with the business of educating children, to the anonymous droves of young queer people who suffered under a state of flagrant, legitimised, public and constant homophobia. Section 28 was a cynical attempt to gain political capital by reigniting centuries-old stigmas and combining them with the moral panic of the AIDS epidemic. It unnaturally extended the fight for equality before the law and in so doing prevented thousands of people from getting the assistance they needed. Though we can celebrate its repeal, the fact it took until the turn of the millennium to happen should be a source of political shame. While we celebrate this milestone, we must keep our eyes trained on the struggles that go on for equal sexual rights, we must not content ourselves with this victory, we must fight on until equality reigns across the globe and the voices of division, discrimination and hatred are silenced.