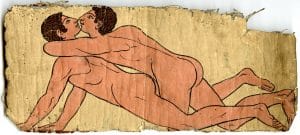

Etruscan painting of two men. As copied in a 19th century drawing of the 5th century BC ‘Tomb of the Chariots’ in a cemetery at Tarquinia, Italy © Trustees of the British Museum

No Offence is a British Museum partnership touring exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Sexual Offences Act (1967) which partially decriminalised male homosexuality in England and Wales. First shown in 2017, and developed in consultation with community partners, the exhibition is on display at the Ashmolean until early December. It is inspired by A Little Gay History: Desire and Diversity Across the World by professor of Egyptology at Oxford University, Richard Bruce Parkinson. We caught up with Parkinson and the exhibition’s curator at the Ashmolean, Matthew Winterbottom as we mark the launch of LGBT History Month (14 November).

Matthew Winterbottom (l) & Richard Bruce Parkinson © David Gowers / Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

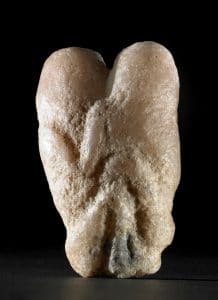

“It’s the oldest known representation of a couple having sex,” Winterbottom says of the Ain Sakhri figures, positioned in one of the Ashmolean’s cases. “You can just about work it out – there’s the two heads at the top, they’ve got their arms and legs round each other. Richard poses the question: why do we assume this is a man and a woman? It could be anybody.”

The Ain Sakhri figures. Palestine, c. 9000 BC. Calcite, 10.2cm high © Trustees of British Museum

“It wasn’t me,” Parkinson promptly points out, “it was Jill Cook” – deputy keeper, department of Britain, Europe & Prehistory at the BM.

The exhibit from 9000 BC, the display’s oldest item, is surrounded by more recent LGBTQ+ campaign badges sporting slogans such as ‘Assume nothing’ and ‘How dare you presume I’m heterosexual’.

“We do slightly suspect it is a straight couple,” Parkinson admits.

“It probably is,” says Winterbottom. The point is, though, we can’t be sure. “History is not black and white, it never has been.”

The badges, the curator tells us, “document the gay rights movement and the cause, and also reference the fact there is still a fight. Some people assume the battle’s been won and that it’s all fine and happy. [But] when you look at what’s happening in America or Russia now, you realise that there’s always going to be a fight for acceptance, recognition and equality.”

“The battle really needs to go on,” states Parkinson. “Institutions like the Ashmolean throwing its weight behind LGBT rights matters a hell of a lot, more than I think people in academia would like to think.”

Nearby the Ain Sakhri figures, in another cabinet, are Roman phallic pendants, “of which there were thousands”, Winterbottom says. “These don’t have a particularly LGBT link, everybody had them, they were good luck symbols.”

© David Gowers / Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

“I do like the lighting,” comments Parkinson – it creates large phallic shadows on the wall behind the objects.

“Very effective,” Winterbottom adds.

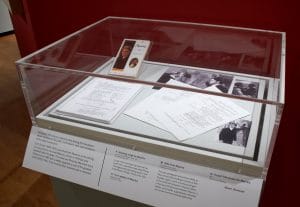

A few feet away sits a copy of the shooting script from the 1987 Merchant Ivory LGBT film Maurice, based on the EM Forster novel (penned in 1913-14 but not published until 1971 – the year after Forster died). James Ivory, who directed and co-wrote the screenplay for Maurice, supplied said script – and viewers can see his comments over it in red pen. Parkinson’s friendship with Ivory (“a lovely man”) formed when he was writing A Little Gay History and approached the movie veteran for film stills. “It was after that friendship that he offered us the shooting script.” For Forster to write a gay novel with a happy ending, he resumes, “was incredibly brave”. Regarding the film, he explains that Marchant Ivory had not long released A Room with a View (also based on a Forster novel) when they brought Maurice out. “The last thing anybody expected in Thatcher’s Britain was that they’d go and film another Forsterian period romance between two men.” Ivory is best-known currently, he says, for his screenplay writing of Call Me by Your Name – “very much an homage to Maurice in some ways”. The director is soon to appear in Oxford, for a Q&A at the Curzon following a showing of Autobiography of a Princess (6 November), and for ‘In-conversation with James Ivory’ at the Sheldonian (7 November).

Merchant Ivory’s Maurice © David Gowers / Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

From Maurice Winterbottom moves us to “more non-European material” and a late 18th century Māori ‘treasure box’ depicting a face engaged in sexual activity. It seems the Polynesian society of this time was more sexually fluid than it would become during the next century. “You can see a penis going into his mouth on one side and his tongue going into a vagina on the other; a kind of oral sex fest going on there. It’s certainly celebrating sexuality, and again it’s not limited to being straight, gay or whatever.”

Māori ‘treasure box’. New Zealand, late-18th century. Wood, shell, 9.4 x 43 x 9.8cm © Trustees of British Museum

“The Māori community is now not as accepting as it was,” Parkinson says.

“That’s because of the colonialism,” Winterbottom remarks. “We exported our homophobia.”

No Offence doesn’t ignore the AIDS epidemic. One example of this being its featuring of the Rainbow Aphorisms series created by Australian artist David McDiarmid – who died from AIDS in 1995. “These were made at the time when having HIV was really a death sentence,” Winterbottom says of the vibrant prints. ‘The family tree stops here darling’ reads one of them. “They’re quite fun to look at, and then you read them and they’re quite dark and troubling.”

Next door to No Offence the Ashmolean has a separate but related exhibition, Antinous: Boy Made God. It chooses not to focus heavily on the relationship country-boy c had with Hadrian, as its co-curator Milena Melfi explains, instead considering his worth without the influence of the Roman emperor. “We’re much more explicit here than next door have been about the relationship between Antinous and Hadrian,” says Winterbottom. “I think we think he was almost certainly his lover, wasn’t he?” he directs to Parkinson. “Who else was he if he wasn’t?”

No Offence’s representation of the relationship is “a little bit visibly suggestive” comes the author’s reply. “It shows how difficult gay history is, because even with the most visible couple in history, nobody actually knows.” Some would ask us to be bold, he says, and state Antinous was definitely Hadrian’s lover. “But you can’t say that, and I think by saying it’s actually not black and white, that’s a very strong political statement to make.”

No Offence: Exploring LGBTQ+ Histories runs until 2 December. Antinous: Boy Made God runs until 24 February ashmolean.org

LGBT HM 2019 takes place in February, with a launch event at the British Library on 14 November lgbthistorymonth.org.uk