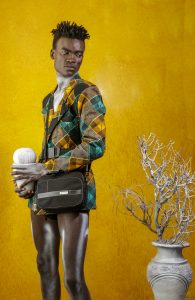

© Shafi Abdi

Passion, Fashion and the Plight of LGBTQ Refugees

Toby Hambly

Lubega Adrac Musa, director of Lunko Haute Couture, speaks to me from a town south of Nairobi, but that’s not where he started life. He’s Ugandan, but was forced to leave the country when his sexuality was discovered. His voice is calm, delicate even, but his words carry unimaginable weight. “It was in 2015 when I had an instance with my family when they attacked me and my boyfriend. So I had to run away for my life and found myself in Kenya. I wouldn’t like to talk about it much. It gives me some bad memories.”

© Shafi Abdi

In 2009, the so-called ‘kill the gays bill’ was introduced by the back-bench Ugandan MP David Bahati. It sought to install the death penalty for homosexuals as well as prison sentences for anyone discovered to have not reported them to the authorities. It has been extensively reported by Jeff Sharlet in Harper’s that there was American evangelical inspiration behind this bill, with consistent links between the Ugandan branch of the US-based religious movement, the Fellowship, and American counterparts. Millions of dollars have poured into Uganda, invested by the Fellowship (also called the Family) into what they call ‘leadership development’. The 84-year-old Oklahoma Senator (Rep) Jim Inhofe, the former Attorney General John Ashcroft and the pastor of one of the largest megachurches in the US, Rick Warren, are regular features of the Ugandan Fellowship’s weekly meetings.

A lot of the rhetoric that supports anti-LGBTQ laws in Africa, alleges that homosexuality is a western import and un-African – Robert Mugabe has publicly called it a “white disease”. This is, of course, morally and factually wrong. The diversity of human sexualities and gender identities outside the cis-heteronormative box exist a priori and not as a function of geography – to allege the contrary requires historical revisionism of a pernicious sort. The fact is that when indigenous religions, moral codes and societal norms prevailed, the situation for whom we now call LGBTQ people was radically different. As Bernardine Evaristo writes in her novel Mr Loverman, “It’s homophobia, not homosexuality, that was imported to Africa, because European missionaries regarded it as a sin.”

© Shafi Abdi

LGBTQ refugees in Kenya face much the same problems as other displaced people. “The common challenges we have,” Lubega begins, “are that we don’t have food, we don’t have shelter, we don’t have transport to our interviews, we don’t have jobs and we lack documents that allow us to stay in the urban setting as refugees.” On top of all this, “we are always attacked by homophobes.” One such attack occurred during a protest outside the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) against a spate of homophobic violence in Kenya’s Kakuma camp.

Before fleeing persecution, Lubega organised fashion shows “in one of the gay bars in Kampala”. He would gather together designers and models, stage an event and try to benefit from a collection. These wound down however. “It reached a time where it was very boring for people because it was on a small scale, the audiences kept on reducing. I had to think of a different alternative of how to survive.” Because of the image he’d acquired, his employment prospects narrowed. “So, believing that I can have my own models, that I have the capacity to produce a fashion show, I was like ‘why can’t I start producing my own clothes as a way of earning a living?’ So I talked to my boyfriend and he was able to buy me a sewing machine, and I was able to teach myself using YouTube tutorials until I perfected it.”

© Shafi Abdi

Lubega operates out of a safe house for LGBTQ refugees shared with Refugee Flag Kenya, organisers of the first Pride parade in a refugee camp. It is there that he teaches his skills to others as part of his mission to provide exposure and training for aspiring designers and models. His label, Lunko Haute Couture holds monthly events where progress is recorded with a professional photoshoot. “I know I’ve reached where I’ve reached because of the skills I have,” he explains, “so I believe if I impart these skills on fellow refugees it will also be very important in their lives, they’ll be able to use these skills to survive.”

His guidance isn’t limited to LGBTQ people, or to refugees: “I believe everybody, regardless of who they are, needs the skills from me.” Allies are welcome too, in a place where being an LGBTQ ally is a more immediate, political proposition than it is here. Since talking to Lubega, the Kenyan High Court has dismissed petitions from activists claiming the colonial anti-LGBTQ law (Sections 162-165) was in violation of the Kenyan constitution. This is disappointing, though it is doubtful whether it will impede the indefatigable Lubega and Lunko Haute Couture. Having been driven from his home, he draws his inspiration “from what God says I am. He knew me before I was born and gifted me with what I am able to do.”